“Bangla Sahib Road,” I would tell the cab driver, adding, quite unnecessarily, “Wahan jo gurudwara hai, na? Wahin.” (You know the gurudwara there?). Despite staying more than once at a hotel across the road from the famous Sikh shrine and having lived in New Delhi for some years, and spending many aimless hours at the […]

“Bangla Sahib Road,” I would tell the cab driver, adding, quite unnecessarily, “Wahan jo gurudwara hai, na? Wahin.” (You know the gurudwara there?). Despite staying more than once at a hotel across the road from the famous Sikh shrine and having lived in New Delhi for some years, and spending many aimless hours at the nearby Connaught Place, I never once made it to the Bangla Sahib. Till a recent trip, when my husband and I had a quiet evening to ourselves, I found myself messaging a friend to ask if she might suggest a gurudwara that we could visit. Bangla Sahib and Rakab Ganj, she said. Go early in the morning, she added, or late in the evening, when it is less crowded, and sit by the beautiful Sarovar.

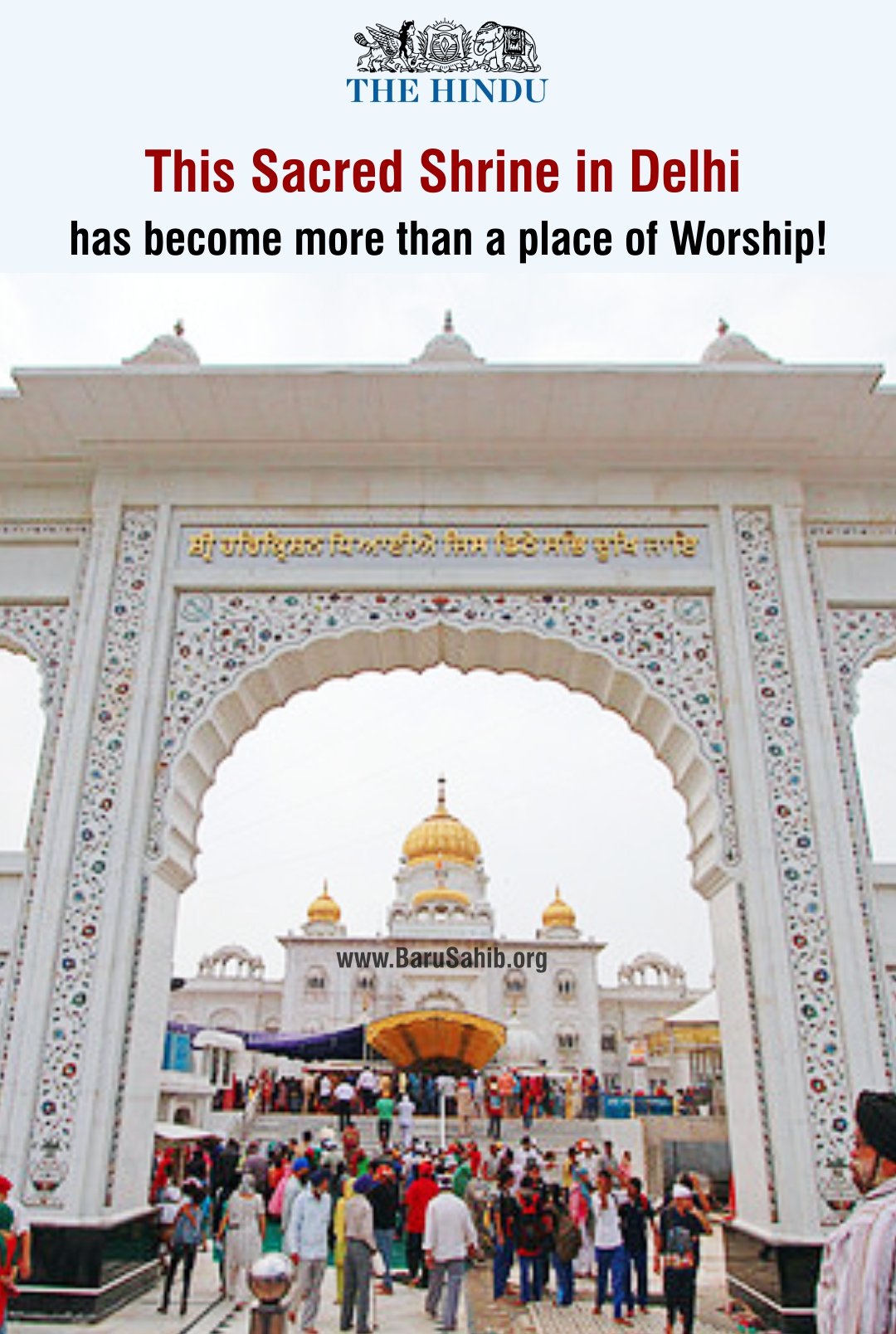

Bangla Sahib is actually situated in a magnificent old estate at the eastern intersection of Baba Kharak Singh Marg and Ashoka Road and, somewhat late on a weekday evening, we joined a ceaseless flow of devotees past enormous arches set with splendid marble inlay work into a vast, self-contained complex in the heart of the national capital.

Open round the clock, offering shelter in the spirit of service, the impeccably tidy gurudwara complex also houses a library, school, hospital, art gallery, and the Baba Baghel Singh Sikh Heritage Museum, named after the warrior who supervised its construction.

Bangla Sahib was once the 17th century haveli or bungalow (thus the name) of Mirza Raja Jai Singh, an important military overlord of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb. Also known as the Jaisinghpura Palace, the historic neighbourhood was demolished by the British to create the circular Connaught Place shopping district, displacing most of its original residents. The saffron-draped Nishan Sahib, the flagstaff signifying the presence of a gurudwara, is befittingly imposing here.

We had just reached the counter manned by karsevaks to hand over our footwear when everyone fell silent in prayer. The sevaks too turned away from the counter to offer their obeisance to the Guru. A dapper Sikh office-goer standing next to us, with laptop bag hung over one shoulder, gestured politely for silence. The routine was restored shortly and we continued up the short flight of stairs towards the gilded hall of worship.

Remarkably, we weren’t once heckled or hurried even though many sought darshan. I was once again struck by the bedrock of spiritual courage and quiet acceptance that prevails in gurudwaras, whether large or small. I had felt it in the modest Army-maintained Gurudwara Charan Kamal Sahib by the freezing banks of the Suru in Kargil, where Guru Nanak Dev, the first of the ten great Sikh gurus, stayed on his journey from Kashmir to Punjab and in bustling Gurudwara Sahib Manikaran in Himachal Pradesh’s Kullu Valley, where the founder guru of Sikhism discovered hot springs in which food could be cooked in the absence of fire.

My memory of a visit to Harminder Sahib, the iconic Golden Temple in Amritsar, is unfortunately lost to the fuzziness of childhood, and serves to remind me that I must go again.

The freshly prepared karah parshad (tokens may be purchased for multiples of Rs. 10) is a delicious halwa made of wheat flour, sugar and ghee. A simple vegetarian meal of rotis, dal, vegetables and kheer is served by volunteers at the langar, the Sikh tradition of offering food as an act of devotion to anyone who needs it.

It was wonderful to sit among families listening to a group of statuesque Khalsas rendering kirtans sonorously under the canopy by the Granth Sahib and, later still, to spend time by the huge Sarovar, full of plump fish. This sacred tank, known to have medicinal qualities, was once the well from which the eighth guru Har Krishan drew water as he cared for the many who took ill in an epidemic of smallpox and cholera in 1664, and he too succumbed in the same year. Raja Jai Singh later donated the grand property as a tribute to the selfless guru.

When we returned to collect our footwear, we found the Sikh gentleman whom we had met earlier behind the counter, volunteering with a jaunty wave of recognition. We were smiling as we made our way out.

Source- The Hindu