Assadullah Asad, 65, a resident of Borwah village in central Kashmir’s Budgam district, started writing and translating Persian poetry soon after he retired from a ‘boring’ job in the planning and statistics department in 2008. He wanted to make some Persian literature accessible in the local Kashmiri language. Since 2008, Asad has written and self-published […]

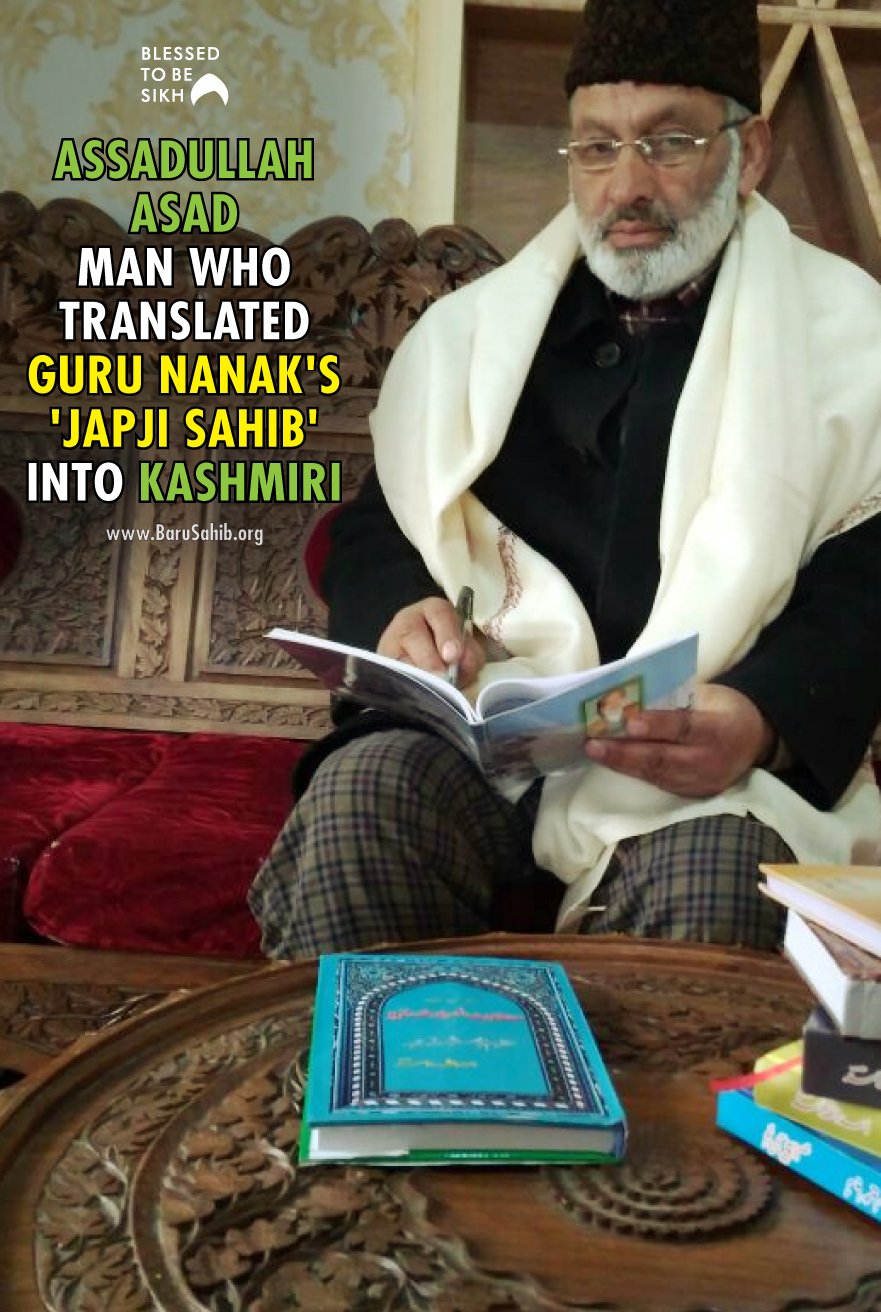

Assadullah Asad, 65, a resident of Borwah village in central Kashmir’s Budgam district, started writing and translating Persian poetry soon after he retired from a ‘boring’ job in the planning and statistics department in 2008.

He wanted to make some Persian literature accessible in the local Kashmiri language. Since 2008, Asad has written and self-published seven books, including one of the first Kashmiri translations of the Sikh holy scripture Japji Sahib. For this, he was appreciated and facilitated by the Sikh community in Srinagar on January 5, which is Gurpurab, the birth anniversary of Guru Gobind Singh.

The organisers had then called Asad’s translation “a big proof of our (Kashmiri Sikhs and Muslims) brotherhood”.

Asad had read a 100-year-old Urdu translation of Japji Sahib a years ago. Last year, he carefully translated the scripture into Kashmiri verse. “I found the teachings in the book and its message of peace relevant, and by translating it, I also wanted to strengthen the bond between Sikhs and Muslims of the Valley, which has stood the test of times,” he said. “The Sikhs have always been like our brothers and they’ve always stood by our side here, even during difficult times in the past decades of conflict.”

Asad is the only Kashmiri writer who has translated the sacred verses of Guru Nanak into Kashmiri language in recent decades. “The Sikh community wants to release the book in the Golden temple in Amritsar,” he said. “I was told that Manmohan Singh has also been sent a copy of my translation.”

After completing the translation, Asad spent his own money to get it published with a local publisher. “I spent about Rs 70,000 on the Japji Sahib translation, so that some copies are made available in bookstalls,” he said. “It was a labour of love and I wanted to keep this book out there for those who wanted to read this holy book of Sikhs in Kashmiri language.”

Soon after his graduation, Asad began his career in the education department in the 1960s, and worked as a contractual teacher for three years. Later, he took up a job in the state’s revenue department, where he worked for nine years, from 1973 to 1982. In 1982, he was employed in the state’s planning and statistics department, where he worked as a statistical officer in Srinagar till his retirement in 2008.

What drew him towards writing and translating Persian texts after his retirement? “My job at the planning and statistics department was laborious and somewhat boring, as I worked mostly with numbers and not words,” he said with a smile. “But after work hours, I would write in my diary every day, hoping to write more after retirement.”

After he retired in 2008, Asad published his first book of poetry, titled Sozi Jigeer (Inner Voice), which was followed by another book of ghazals in Kashmiri, Laove heath gulale (Wet Tulips) in 2010. A year later, he came up with another book of poems in Kashmiri language, which was titled Dukh te daag (Miseries and scars), containing 100 Kashmiri ghazals which touched on the political and everyday life in the Valley.

In 2012, Asad translated into Kashmiri Allama Iqbal’s Persian book Pas Che Bayad Kard (What should then be done, O people of the East). Iqbal wrote it in Persian in the last years before his death, he said, and it is considered to be his seminal work. Published in 1936, the philosophical poetry book touches on themes of poverty, the role of women, art, literature and politics in the East and West. “If someone hasn’t read any work of Iqbal and only reads this book, he will be able to understand all his work and philosophy,” said Asad.

In 2013, he published another 500-page book of his own Urdu poetry titled Naqsh e Faryadi.

“I was drawn towards reading and writing from my graduation days, but I didn’t get much time to write during my government service,” he said, adding that he studied subjects like mathematics, political science and Persian in college. In the following years, he came to read a lot of poetry and other literature in Persian. “Persian was taught well in our colleges by excellent teachers, and even at school level from the sixth standard onwards.”

The apathy shown towards Persian in the Valley over the past several decades has pained Asad. “Our youth can’t read and write in Persian now, which is such a beautiful language with rich and unparalleled literature,” he said, adding that a lot of literature on Kashmir is originally written in Persian.

He blames successive state governments and policy makers for the death of Persian in Kashmir. “A wealth of our rich cultural and literary heritage is originally written in Persian,” he said. “But not learning this language and abandoning it, we are distancing ourselves from our rich cultural and literary heritage.”

Out of his seven books, he submitted one of his translated works to the state-run Jammu & Kashmir Academy of Art, Culture & Languages a few years ago. But it wasn’t published in the end. “They had approved it initially and it was praised by noted writers and poets of the Valley, but it didn’t get published in the end,” he said. “After that, I decided not to send any of my work to the academy.” However, he continued to write and translate, spending his own money to publish.

In 2016, Asad says he was the first Kashmiri writer to translate Persian verses of Sufi poet Amir Khusrow into Kashmiri verse. Titled Ghazliyat-i-Ameer Khusrow, Koshur Tarjame (Kashmiri translation), the book contains 120 ghazals by Amir Khusro translated into Kashmiri verse. “There was no Kashmiri translation of his work and I wanted to do one,” he said. “It is said Amir Khusrow had written so much that it could fill a whole library. He could read and write in 19 languages.”

Being seeped in the Persian language and literature has made Asad adept in translating Persian poetry into Kashmiri verses. “While translating the verses into Kashmiri, I take care that the theme is retained and the essence, the sweetness and the soul of poetry is transferred from one language to another,” he explained.

Asad is presently translating the shrukhs (verses) of the patron saint of Kashmiris, Sheikh ul-Alam, which he’s been working on for the past two years. He hopes to complete the translation this year. “I’ll be translating about 360 rubayats (quadruplets) into Persian language. This will be the first time a Kashmiri writer will be publishing a Persian translation of his kalaam.”

Asad laments that the book reading culture is on a decline as people spend more time on smartphones and social media. “We have less readers for books now, especially for books written and translated into Kashmiri language,” he said, adding a note of hope, “But books are the best sources of knowledge and no experience is as fulfilling as book reading.”

I asked him how his poetry books and Kashmiri translations will find more readers beyond his hometown. He recalled a line by the famous English writer Jerome K. Jerome: “If you don’t rise to us, we cannot stoop to you…”

Majid Maqbool is a journalist and editor based in Srinagar, Kashmir

-TheWire