Maj. Kamaljeet Singh Kalsi stood backstage at the Democratic National Convention, watching through tears as the parents of a fallen Muslim-American soldier delivered a powerful message about sacrifice and the dangers of discrimination. As a Sikh, Kalsi does not share the Muslim faith of Khizr and Ghazala Khan and their slain son, Army Capt. Humayun […]

Maj. Kamaljeet Singh Kalsi stood backstage at the Democratic National Convention, watching through tears as the parents of a fallen Muslim-American soldier delivered a powerful message about sacrifice and the dangers of discrimination.

As a Sikh, Kalsi does not share the Muslim faith of Khizr and Ghazala Khan and their slain son, Army Capt. Humayun Khan. But he found common cause in their call for Americans to honor military service and sacrifice regardless of one’s religion.

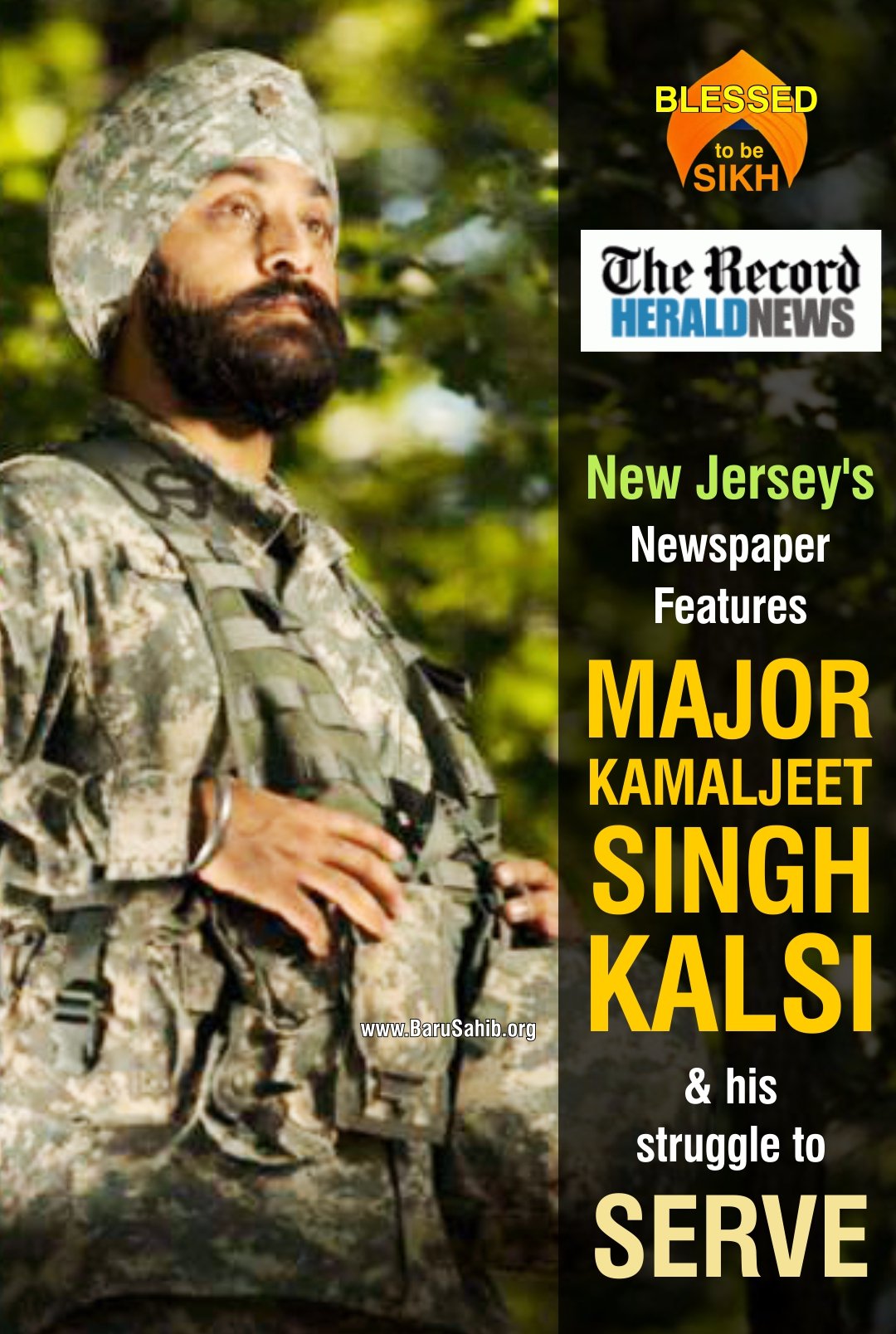

That night Kalsi wore a black suit and tie, in addition to the pink turban that holds his unshorn hair, both symbols of his faith. His work clothes — the uniform of a U.S. Army officer — includes a camouflage-pattern turban.

It’s the embodiment of a small victory in a battle he’s waged with the military establishment over a rule he believes restricts the opportunity of Sikhs and members of other religious groups to serve in the armed forces.

The 40-year-old Riverdale resident who grew up in Lodi is believed to be the first Sikh soldier to be allowed to wear his articles of faith while in uniform since the military in 1981 imposed a ban on facial hair and other religious symbols deemed to not fit into its uniform appearance standards.

To be sure, Kalsi has opened a window for those like him. But his breakthrough has been limited. Others who want to serve with outward manifestations of their religious identity intact must still go through the same arduous process as he did, which can last up to a year, and approval is not guaranteed.

So he continues to push for such restrictions to be removed entirely, allowing Sikhs and members of other religious communities to serve more freely.

There are five recognized articles of faith Sikhs typically wear. Here’s the meaning behind each one:

Kes (unshorn hair) — Hair kept in its natural state is regarded as part of living in harmony with God. Wearing a turban declares a commitment to the faith.

Kangha (comb) — A small comb worn in the hair symbolizes a clean mind and body.

Kara (steel bracelet) — The bracelet serves as a reminder that the practitioner serves the faith’s Guru, or leader, and does not do anything that would shame or disgrace the faith.

Kirpan (sword) — The sword, at times a small dagger, symbolizes the Sikh’s obligation of courage, self-defense and the capacity and readiness to defend the weak and oppressed.

Kachhehra (soldier’s shorts) — The shorts remind Sikhs to maintain high moral character and practice self-restraint over passions and desires.

Source: The Sikh Coalition; BBC.

For his efforts, he is one of nearly 40 people being honored by the Sikh Coalition this month in a portrait exhibit of Sikh-Americans to mark the 15th anniversary of the coalition and its efforts to raise awareness of the Sikh community’s contributions to American society.

IF YOU GO:

The Sikh Coalition is hosting a portrait exhibit of Sikh-Americans to mark the 15th anniversary of the coalition and its efforts to raise awareness of the Sikh community’s contributions to American society. The exhibit, at 530 Broadway in Manhattan, will open Saturday and is slated to run through Sept. 25.

Beard, turban included

In early 2001, while Kalsi was in medical school in California, Army recruiters came to the campus looking for doctors. He told them he would love to serve but that he came with a beard and turban.

The recruiters said it was fine.

So Kalsi joined up in the Reserve and reported for duty at West Point and various posts while he finished medical school.

Once he became a doctor, though, the Army called. He told commanders at his new assignment that he was an observant Sikh who kept a beard and wore a turban. The officers said they would check, but once again, he was assured that all would be fine.

“A month later, I got a very different call,” Kalsi said. The brass had looked at the 1981 regulation and said Kalsi would have to shave his beard and remove the turban.

Major Kamaljeet Singh Kalsi is the first known Sikh to receive a religious exemption to wear his religious articles while serving in the U.S. Army. Kalsi in the backyard of his home.

“I said, ‘Look, sir, when the time comes I’ll bleed for my country. I’ll die for my country,’Ÿ” Kalsi said. “But I can’t give you that which doesn’t belong to me. I can’t give you my faith. I can’t give you the turban and my hair which belongs to my God.”

Eighteen months later, in 2010, the command relented, allowing Kalsi to wear his turban and other articles of faith when he deployed to an isolated combat hospital in war-torn Helmand Province, Afghanistan, during the troop surge ordered by President Obama.

“We saw some of the bloodiest injuries of the war. But none of the soldiers ever stopped me and said, ‘Don’t take care of me because you have a beard, don’t take care of me because you’re wearing a turban,’Ÿ” Kalsi said.

Sikh population estimates in the United States range from 200,000 to 500,000, with roughly a quarter living in the New York metropolitan area, according to figures from the Sikh Coalition. Many families have been in the U.S. for four generations or longer. Sikhs arrived on the West Coast in the 1800s and helped build the Transcontinental Railroad.

Despite their history, they have been the target of hate crimes, which the Sikh Coalition said have increased since 9/11.

Acting Bergen County Prosecutor Gurbir Grewal, who is a Sikh, said confusion about the tenets of their beliefs have made Sikhs an easy and repeated target for discrimination. During the Iranian hostage crisis in the 1970s, people would confuse Sikhs with Iranians. During problems with Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi in the 1980s, people thought Sikhs were Middle Eastern. During the Persian Gulf War in the early 1990s, people thought they were Iraqi.

Woven into the cultural and religious identity of an observant Sikh man are both the outward symbols of his faith and the willingness to take up arms, both literally and figuratively.

Early in the life of the faith, during the rule of Mughals,a Muslim empire that controlled large portions of India from the 1500s to the 1800s, Sikhs were persecuted, driven to near extinction and told they could not wear turbans, grow beards or carry weapons.

During this period, Sikhs established a military tradition that has lasted to this day, calling on the men to become “soldier saints” and not to hide the articles of their faith, which, beyond a beard and turban, include a bracelet and a small sword or dagger.

Grewal, a childhood friend, said that Kalsi embodies much of what is taught to young Sikhs — to stand up against injustice and to serve the larger community.

The prosecutor was working in a private law office across from the Pentagon on 9/11 when planes crashed into the Twin Towers and the U.S. military headquarters. He left private practice to become an assistant U.S. attorney, serving in Brooklyn and Newark before taking over as prosecutor.

Growing up in suburban New Jersey in the late 1980s and ’90s, they did not see many Sikhs, both Kalsi and Grewal said.

Kalsi said Grewal and other young Sikhs a few years older helped him through those times.

Even while serving in the Army, Kalsi has noticed increased scrutiny at airports along with veiled and not-so-veiled derogatory comments from people calling him “Osama” or telling him to “go back where he came from.”

Despite these attitudes, Kalsi said, young Sikhs still want to join the military. He fields weekly phone calls from young Sikhs interested in serving.

But for now they must complete a burdensome application process for an exemption or remove their articles of faith, he said.