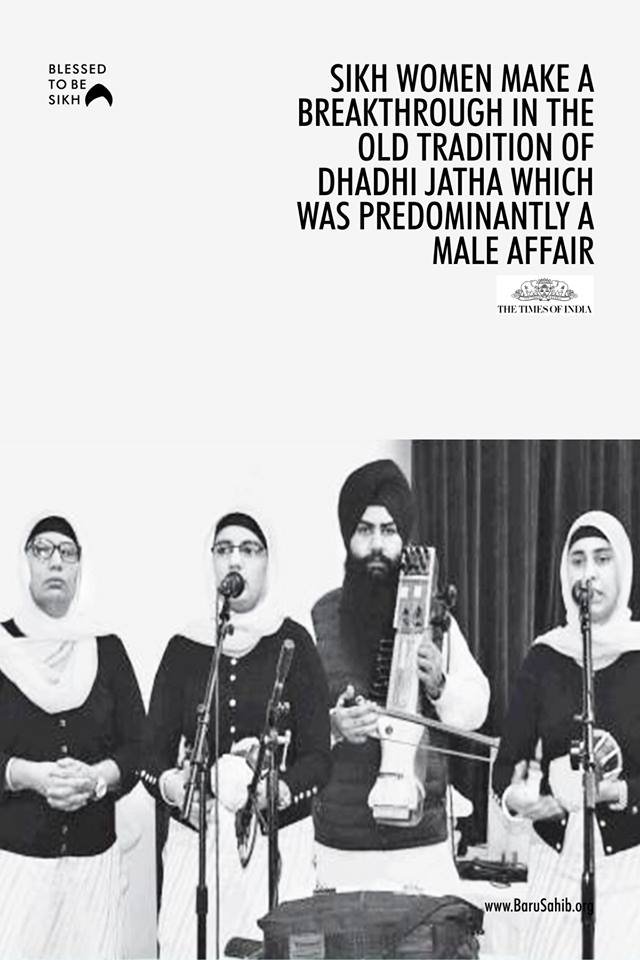

For over three and half centuries, dhaadi jathas (ballad singers), who enthralled the Sikh community with their highpitched singing, were exclusively men. It is only in the last few decades that women have taken up this genre of traditional music. They may have started late, but they have certainly melted hearts with their fervent singing […]

For over three and half centuries, dhaadi jathas (ballad singers), who enthralled the Sikh community with their highpitched singing, were exclusively men. It is only in the last few decades that women have taken up this genre of traditional music. They may have started late, but they have certainly melted hearts with their fervent singing and have received wider acceptance.

“The trend of women dhaadi jathas started in the mid-’90s. There was never really a ban on women – women doing Gurbani Kirtan in gurdwaras has been a common practice – but they somehow did not take to it before then. Though this style of singing existed outside religious circles, but it always remained a male affair,” says Gurdial Singh Lakhpur, president of Miri-Piri International Dhaadi Sabha.

Sisters Gurdeep Kaur Neetu and Rajbir Kaur Bhago, who started singing in the mid-’90s are among the pioneers —“If not the very first, we are among the first few women dhaadi jathas,” they insist. Their jatha is called Barnale Walian Bibian da Jatha. “In 1996, our first audio cassette was out. We were only in school then. Our mother was very keen that we should learn this style of singing, as her father was an amateur sarangi player. She motivated us,” says Neetu.

Now they are a part of a jatha led by Balbir Kaur, who hails from village Khaira.

Kaur’s is a story like no other. Not content to do just household chores, and having been denied education beyond Class X, she rebelled after marriage, with her husband firmly by her side. “Since childhood I was passionate to do something with my life. A few years into my marriage, I thought of forming a dhaadi jatha and my husband then learnt sarangi. About 13 years ago, we formed our three-women jatha and my husband plays sarangi,” says Kaur.

For Sarabjeet Kaur from village Benapur in Jalandhar, who is one the few women sarangi players, sarangi has become her identity. “I was the second woman who began playing sarangi, first was with a jatha from village Ranipur,” she tells proudly. She started her all-women jatha in 1997. For her it was a natural thing to do, as both her husband and brother were dhaadi jathas.

When her husband died in 1996, she decided to continue the profession. “Now I feel like discontinuing with jatha, but when old acquaintances invite with a lot of respect and affection, it is difficult to say no,” she says.

What distinguishes a male-led dhaadi jathas from women groups is the fact that male jathas are known by the name of the orator, who needs to be well versed in Sikh history and related issues. Women jathas are usually named after singers.

“Interestingly, even if it is not all-women jathas, but one with only two or three women members, it is still named after women,” says Saroop Singh Kadiana, a prominent dhaadi jatha and president of Gurmat Parcharak Sabha Doaba. She also contested assembly election on AAP ticket from Phillaur in 2017, but lost with a narrow margin.

Like in the case of Lakhwinder Kaur, from village Khangoora, near Phagwara, a sarangi player with Khangoore Walian Bibian da Jatha. Though her husband Lakhwinder Singh is a lecturing member, but the jatha is known as woman’s jatha. “We formed an all-women jatha in 2000. We were known as Phagware Walian Bibian da Jatha, as we used to stay in Phagwara. Then two members got married and our group disintegrated,” says Kaur. When she married Lakhwinder Singh, who was already a dhaadi, they formed a jatha and it was named Khangoore Walian Bibian da Jatha.

Amandeep Kaur of Nakodar has a similar story. She formed an all-women jatha when she was still studying. But after her marriage in 2007, she formed a new jatha in her name, even though her husband Gurjit Singh is hersarangi player.

Parminder Kaur traces a similar journey. She started her group with her sister around 15 years ago and it was an allwomen group. “After marriage we dispersed,” she says. Now, as she lives in village Barsaalan, also in district Jalandhar, she named the group after her and the village – Barsaalan Walian Bibian da Jatha. Her husband is happy to be an accompanist, playing sarangi for her.

Another thing that made the journey of women jathas different from that of the parallel narrative — in which women almost always had to struggle to get any kind of acceptance — they may have broken tradition, but women jathas found acceptance almost immediately.

“We have been to Canada thrice and people treat us very respectfully,” says Amandeep Kaur of Nakodar.

Balbir Kaur, whose jatha is called Pasle Walian Bibian da Jatha, says her parents were reluctant when she said that she wanted to become a stage singer, but they readily agreed when she wanted to form a dhaadi jatha. “In 2010, I sang a dhaadi vaar in Youth Festival of Guru Nanak Dev University with some girls and we won the first prize. Later, I formed a jatha with my elder sister,” says Kaur.

Kaur takes pride in the fact that her dhaadi jatha gets equal invitations for programmes as her male counterparts. “I had taken music as a subject in college, later did post graduation in it and naturally wanted a singing career. I also wanted to have my own identity and now my parents and relatives take pride in me,” says Kaur.

Times of India

1 Comment